An Unruly Roundup Of America’s First Bohemians

Huffington Post, September 2014When people think of counterculture, the 1960s tends to come first to mind. But one of America’s most important alternative movements emerged a full century earlier, during the late 1850s. On the eve of the Civil War, a tumultuous time not unlike the Vietnam era, a colorful group of artists and writers gathered at Pfaff’s saloon in Manhattan. They were America’s first Bohemians.

The so-called Pfaff’s Bohemians led a transition from stuffy, genteel art to art that was bold, brazen, in-your-face. They paved the way for such modern artist provocateurs as Dave Eggers, George Carlin, and Lena Dunham. Sadly, America’s vanguard Bohemians have been mostly forgotten. Aflame with creativity, they burned out fast, often slipping into obscurity or dying young, as Bohemians are wont to do. Walt Whitman is the lone representative of the once-famous Pfaff’s scene who remains well known to this day. Even Whitman tends to be thought of as a beatifically shaggy old man — the enduring “Good Gray Poet” image — rather than as the young radical that hung out in a saloon.

Illustration of Pfaff’s saloon

I’ve just written the first book ever about the Pfaff’s set, Rebel Souls: Walt Whitman and America’s First Bohemians (Da Capo Press, September 2). Reconstructing their story demanded a great deal of digging, but it was rewarding to revive this long-lost artists’ circle. What follows are sketches of some of its main figures:

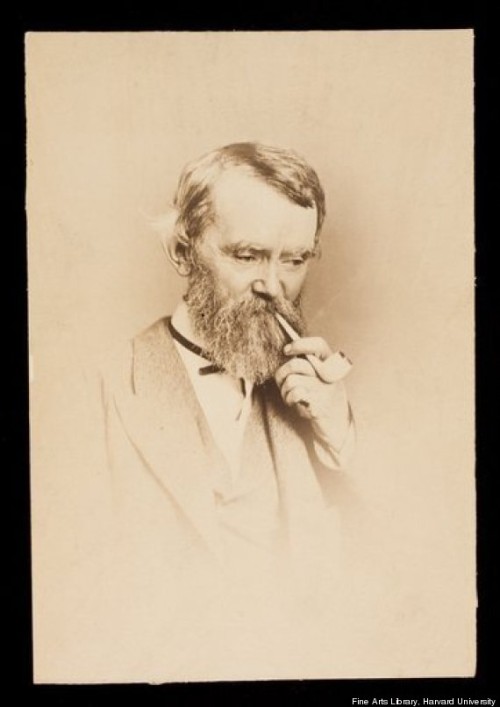

Henry Clapp, Jr.

Clapp gets credit for bringing Bohemia to America. During the 1840s, as an esteemed professional lecturer on topics such as abolitionism and temperance, he often shared the stage with the likes of Frederick Douglass. In 1849, Clapp traveled to Paris to attend a three-day world peace conference. His timing was perfect: the city’s wild Left Bank scene was exploding. Clapp — to this point a teetotaler — fell off the wagon and into Bohemia. He wound up staying in Paris for three years. When he returned to America, he was intent on introducing the French-style Bohemia he’d so enjoyed. Soon, he happened upon Pfaff’s (address: 647 Broadway), which struck him as having the perfect libertine atmosphere. The saloon’s proprietor set up Clapp in a separate room featuring a long table that could seat roughly 30 people. Now, it was just a matter of assembling a group of Bohemian artists.

Clapp, smoking his trademark clay pipe, an affectation from his Paris days.Â

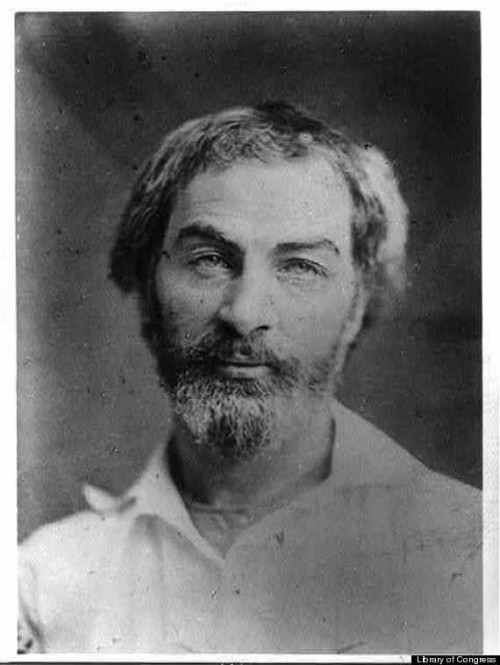

Walt Whitman

Whitman was Clapp’s most illustrious recruit. When Whitman joined the Bohemian circle, he had already achieved a small reputation. But lately, he’d fallen into a personal and artistic slump. Unemployed, Whitman was living with his mother and several siblings in a crowded Brooklyn basement apartment. Pfaff’s saloon was a welcome haven for the poet. “I think there was as good talk around the table as took place anywhere in the world,” he would recall. Time among his fellow Bohemians was crucial to Whitman’s development as an artist. During his Pfaff’s period, he wrote more than 100 new poems, addressing such bold subjects such as America’s fast-dissolving union and romance between men. Many of these poems appeared in the landmark 1860 edition of his masterpiece, Leaves of Grass.

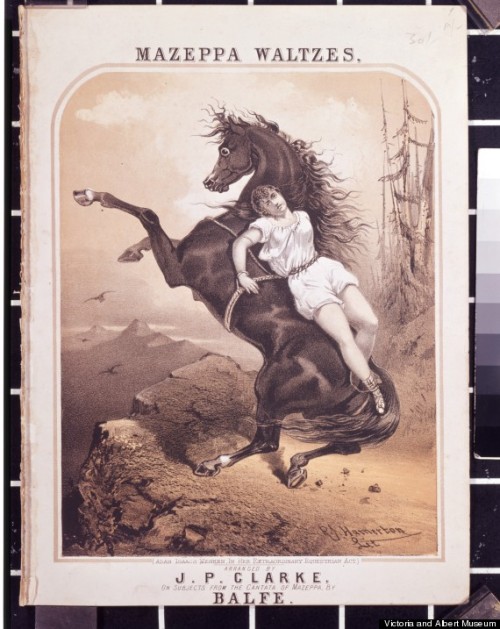

Adah Isaacs Menken

Menken, an actress and poet, was one of the most fascinating personalities at the saloon’s long table. By turns calculating and vulnerable, she was like a sepia-tone Marilyn Monroe. Her signature role was in the risque equestrian drama, Mazeppa. She performed the play in drag, as a Tartar warrior who is stripped down by his enemies, revealing the buxom actress underneath. She was then bound spread-eagle to a real-live horse. Mazeppa was a box office sensation during the Civil War and made Menken into a big star, one of the nineteenth century’s greatest sex symbols. She even took her play to England, where Dickens attended several performances and visited the actress backstage. Then, it was across the Channel, where an alleged affair with Alexandre Dumas set all France abuzz. Despite her success, Menken managed to die penniless in Paris, aged 33 — a true Bohemian.

Illustration from Mazeppa of Menken strapped to horse

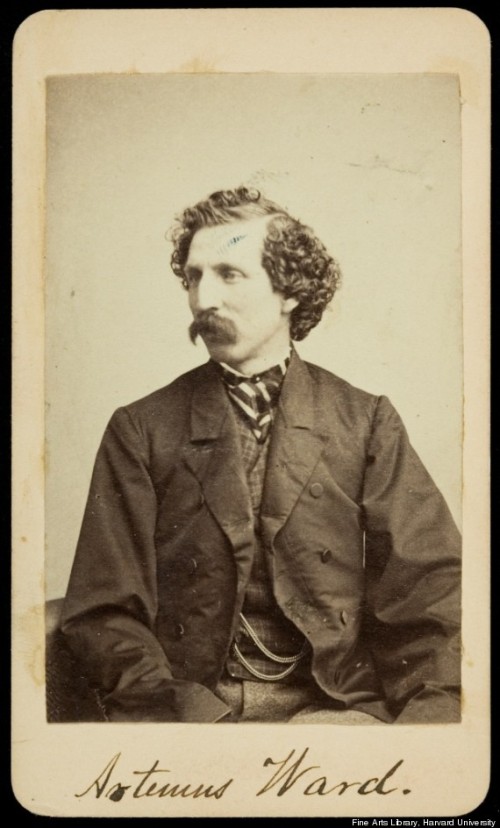

Artemus Ward

Pfaff’s denizen Artemus Ward was so revolutionary that his contemporaries lacked a term for what he did. Newspapers often called his act a “comic lecture.” But he deserves credit as America’s first stand-up comedian. Lincoln was a huge fan. Before unveiling the Emancipation Proclamation to his cabinet, he read aloud to them some of Ward’s comic stylings. “With the fearful strain that is upon me night and day,” the president explained, “if I did not laugh I should die, and you need this medicine as much as I do.” While touring the West with this act, Ward became friends with another pioneering American humorist: Mark Twain.

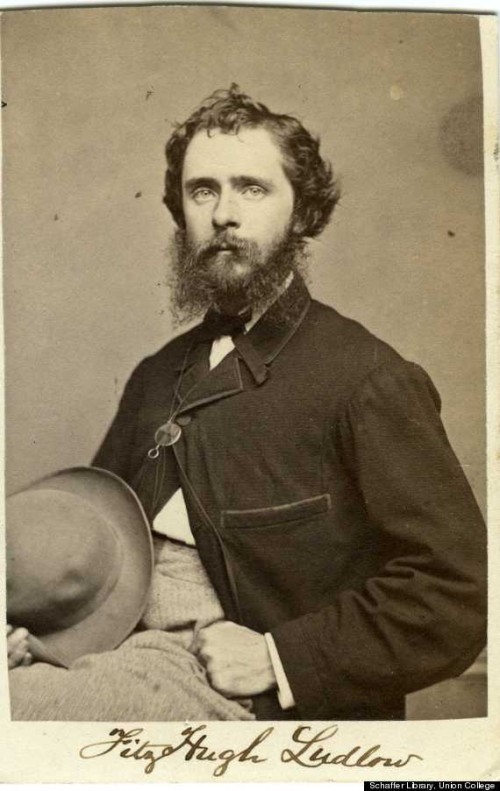

Fitz Hugh Ludlow

As a 21-year-old wunderkind writer, Ludlow published The Hasheesh Eater, one of the best-selling books of 1857. It detailed such experiences as blissed-out music appreciation, giggle fits, the munchies, and — because he ingested huge doses — vivid hallucinations. Such experiences, familiar today, were radical at the time. Ludlow’s book even launched a brief hash fad (the concept of illegal substances didn’t even exist yet). Many Americans were inspired to try the drug, including John Hay, then a student at Brown, later Lincoln’s personal secretary. He’d recall the university as a place “where I used to dream dreams and eat Hasheesh.” A century later, LSD guru Timothy Leary would describe himself as being in the “alchemic-shaman tradition of Paracelsus, Ludlow, and William James.” Indeed, this highlights one of the most intriguing things about Ludlow, Whitman, Menken and the rest of America’s first Bohemians — they’re so very of their time, yet so startlingly timeless.